MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

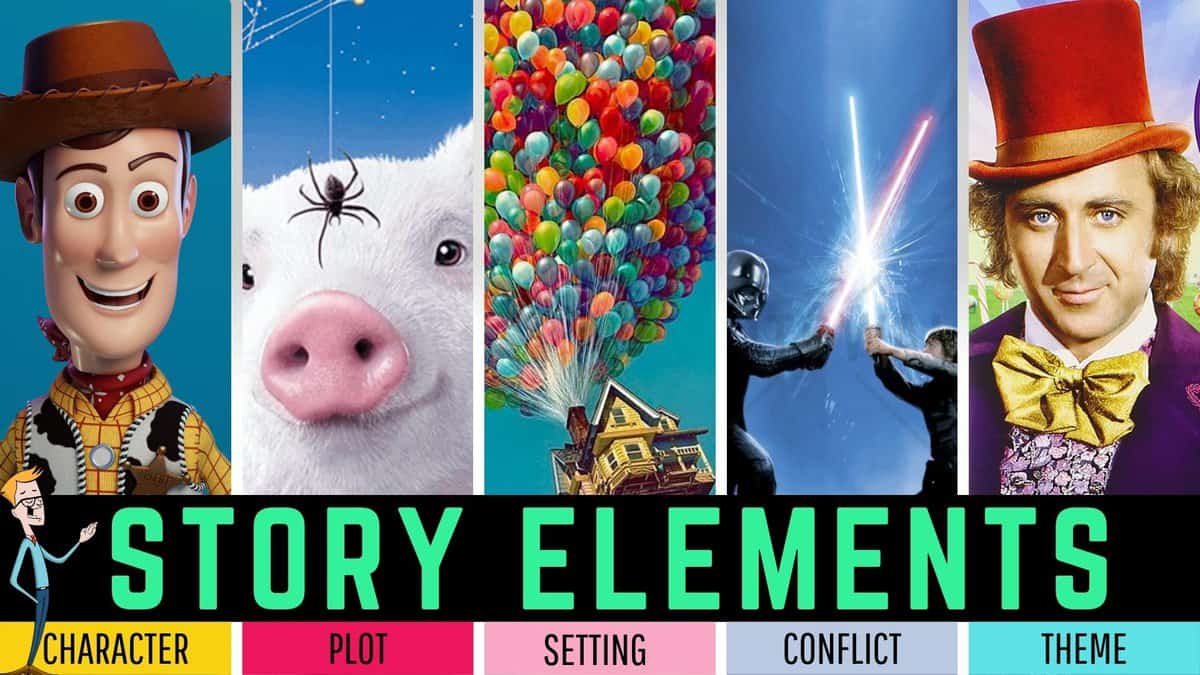

Here, we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution. We will also look at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events, characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing.

We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here.

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

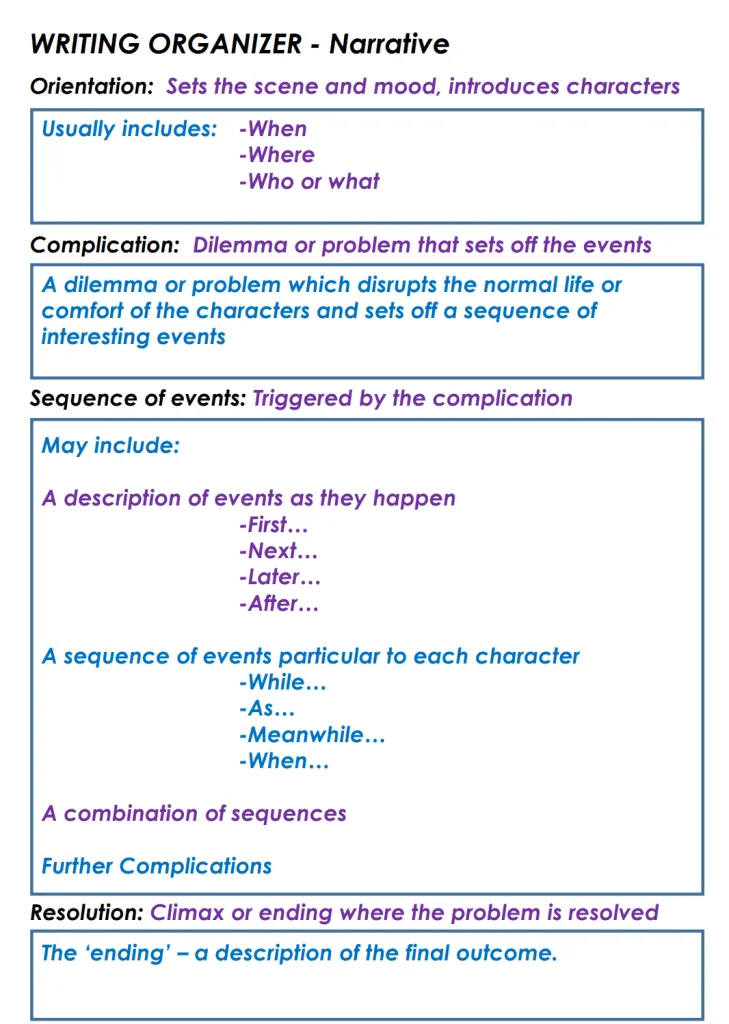

NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

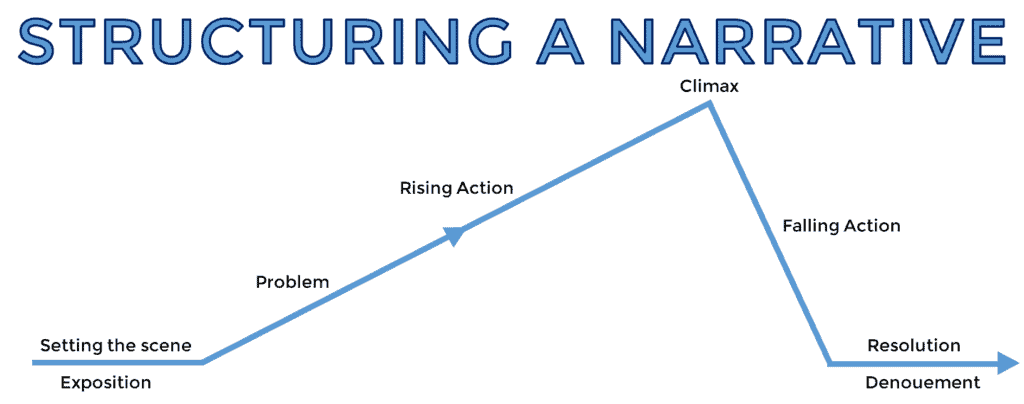

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events.

Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It highlights the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, helping you see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story.

However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs, and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading.

For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods.

If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for younger students.

It leads naturally to the next stage of story writing: creating suitable characters to populate the fictional world they have imagined.

However, older or more advanced students may wish to challenge the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They might do this for comic effect or to craft a more original narrative.

For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. In fact, it may lure the reader into a sense of nostalgia or happy reverie as they recall their own birthday celebrations. This creates a sense of vulnerability, making the shocking action that follows even more impactful.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts.

If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the center of the relationship between the writer and the reader.

That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality.

Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way to achieve this is through writing that appeals to the senses.

Encourage your student to reflect deeply on the world they are creating:

- What does it look like?

- What does it sound like?

- What does the food taste like there?

- How does it feel to walk those imaginary streets?

- What aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, consider the when, or the time period.

- Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic?

- Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London, with human waste stinking up the streets?

If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- School

- Village/town

- Island

- Castle

- Jungle

- Farm

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your students have created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories typically require only one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater rather than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters can confuse readers and become unwieldy within a limited canvas. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, there are strategies to help. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on real people they know. This approach can make the task less daunting and taxing on their imagination.

Whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or describing the characters’ physical and personality traits can be an effective prewriting activity. Students should consider in-depth details about their character:

- How do they walk?

- What do they look like?

- Do they have any distinguishing features?

Small details, like a crooked nose, a limp, or bad breath, bring life and believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and let their imaginations fill in the rest.

Younger students often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their craft, students need to understand when to transition from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly important when developing characters.

Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through their actions rather than merely stating their virtues or faults. For example:

- A character who walks with their head hanging low, shoulders hunched, and avoids eye contact demonstrates timidity without the word ever being mentioned.

- A character who sits down at the dinner table and immediately snatches up his fork, stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even sat down, shows a tendency toward greed or gluttony.

These subtle details create richer, more engaging characters while improving the quality of the writing for the reader.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events.

For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals.

In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Kindness

- Bravery

- Curiosity

- Determination

- Honesty

- Loyalty

- Imagination

- Compassion

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here, but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area where apprentice writers face the most difficulty.

Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. In a short story, the problem usually centers on what the primary character wants to happen—or wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome, and it is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that the events of the story unfold.

Even when students grasp the need for a problem in their story, their completed work may still fall short. Often, this is because, in real life, problems frequently remain unresolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome, and students instinctively reflect this in their stories.

In everyday life, we often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved, and we accept this as part of life. However, this approach doesn’t work well for storytelling.

In a story, the problem must eventually be resolved, one way or another. Whether the character successfully overcomes their problem or is decisively crushed in the process is less important than ensuring the conflict reaches a conclusive resolution.other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs man

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story.

It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense, making the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, which is what makes a story great.

So, next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient. Without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action.

It is the moment when the struggles ignited by the problem come to a head. The climax determines whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. At this pivotal point, two opposing forces face off until the bitter (or sweet!) end, and one ultimately emerges victorious. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases, leaving the reader wondering which force will prevail. The climax is the release of this tension.

The success of the climax heavily depends on how well the other story elements are crafted. If the student has developed a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and care for, the climax will pack a more emotional punch.

The nature of the problem is equally critical. It defines what’s at stake in the climax. For the climax to resonate with the reader, the problem must matter deeply to the main character.

Encourage students to engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Ask them to reflect on the storyline and identify the most exciting moments:

- What was at stake at these moments?

- What did you feel in your body as you read or watched?

- Did you breathe faster, grip the cushion hard, or notice your heart rate increase?

This is the effect a good climax has—and what students should strive to achieve in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions may remain unresolved for the reader, even if the main conflict has been resolved.

The resolution is where those lingering questions are answered. In a short story, the resolution may only be a brief paragraph or two, but it is usually necessary. Ending a story immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students is to point to the traditional ending of fairy tales: “And they all lived happily ever after.” This “weather forecast for the future” provides closure and allows the reader to take their leave. Encourage students to consider the emotions they want to leave their readers with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is typically complete by the end of the climax, the resolution is often where a twist may appear—think of movies like The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly requires significant skill and could serve as a challenging extension exercise for advanced students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories:

- The hero achieves their goal.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Balance is restored to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- The character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- The character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, and more—but not before!

Storytelling involves both craft and art. If technical accuracy is pushed too early, it can cause storytelling paralysis, hindering creativity. It is essential to give students the freedom to make mechanical mistakes in their language use during the creative process, which they can correct later.

Good narrative writing is a complex skill that takes years to develop. It challenges not only the student’s technical language abilities but also their creative faculties.

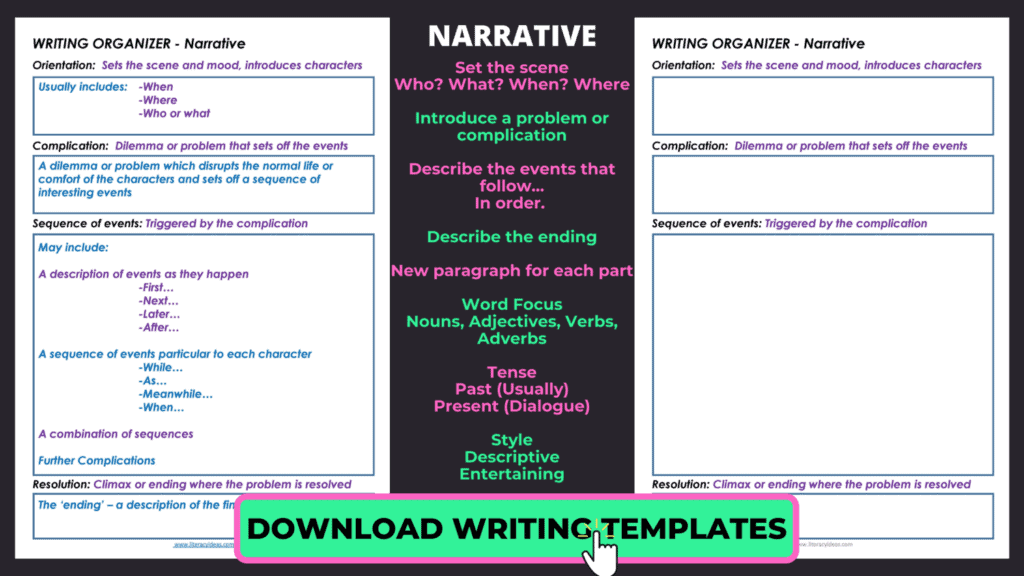

To support students as they develop these skills, use tools like:

- Writing frames

- Word banks

- Mind maps

- Visual prompts

These resources can offer valuable guidance as students work through the wide-ranging and challenging skillset required for great storytelling.kills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

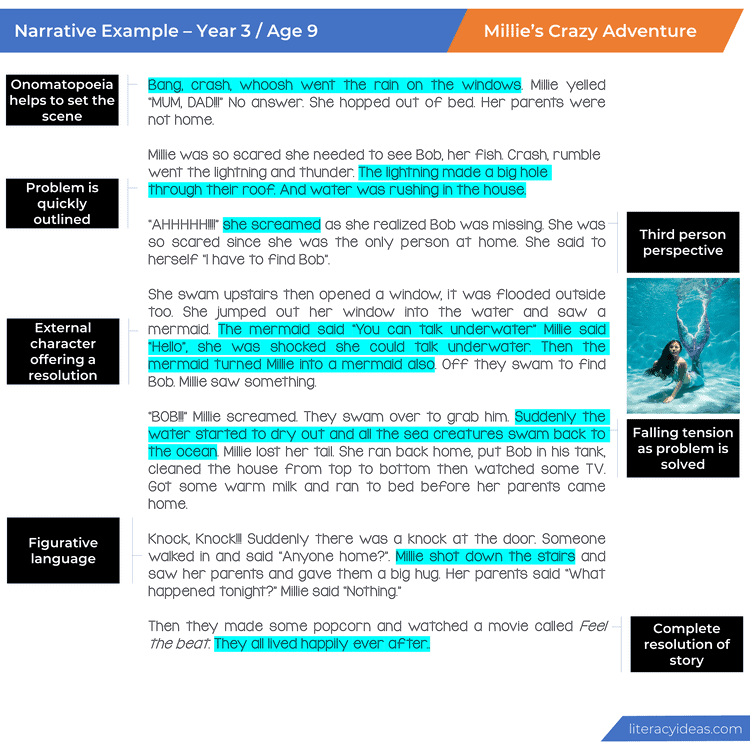

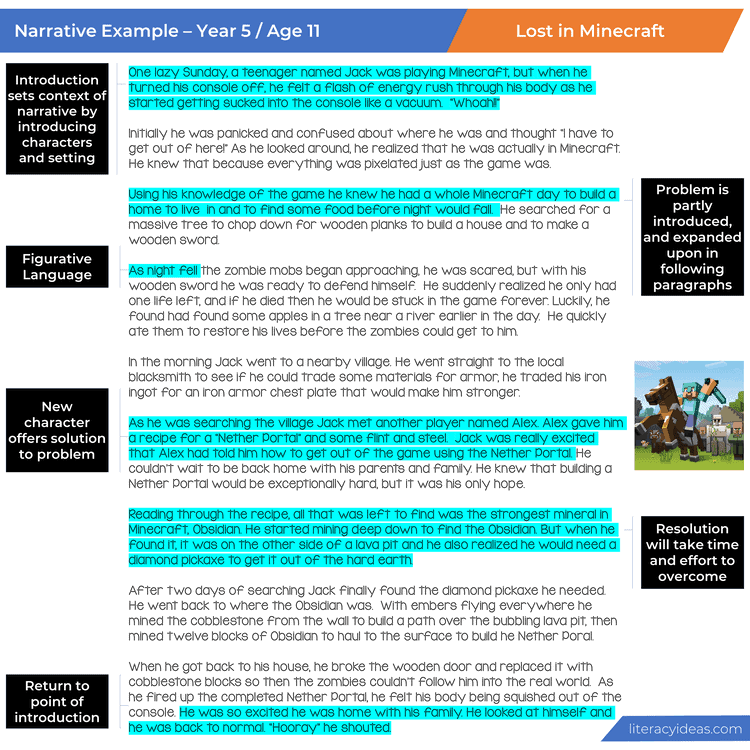

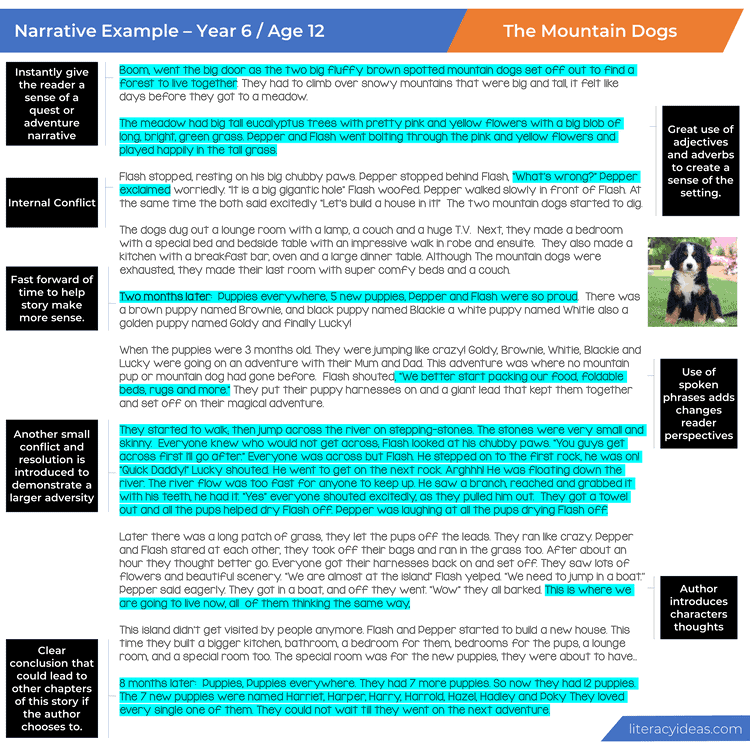

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow.

- There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)