WHAT IS AN INFERENCE?

We’ve all been there at some point; a blank-faced student stares back at us in response to our question and states, “I don’t know, teacher. It doesn’t tell us in the story.” Usually, this response has been incited by an inferential question, but what exactly is an inference?

(An) Inference can be defined as the process of drawing a conclusion based on the available evidence plus previous knowledge and experience. In teacher-speak, inference questions are the types of questions that involve reading between the lines.

Students are required to make an educated guess, as the answer will not be stated explicitly. Students must use clues from the text and their experiences to draw a logical conclusion.

Students begin the process of learning to read with simple decoding. From there, they work towards fully comprehending the text by learning to understand what has been said, not only through what is explicitly stated on the page but also through what the writer has implied. It is this ability to read what has been implied that the term inference refers to.

For example, if we come across sentences such as:

He placed his hand firmly on her back and ushered her hurriedly out the door. “Yes, yes, yes. I will call you soon to set up another meeting. I will!” George said, punctuating the end of his sentence with a firmly shut door.”

In this extract, the writer does not explicitly state that the man in the story wants to eliminate the person he is addressing. However, he implies this is the case through the action he describes. Reading this correctly is to infer. To imply is the throw, to infer is the catch.

WHY TEACH INFERENCE?

Teaching inference skills is fundamental to our student’s development as critical thinkers. It is a higher-order skill that is essential for students to develop to afford them access to the deepest levels of comprehension.

Having a finely tuned ability to infer also has important applications in other subject areas, particularly Math and Science. Given the centrality of pattern reading in these two subjects, it is no surprise that students will find these skills instrumental in prediction and evaluation.

Being able to infer from clues develops in our students an appreciation of the importance of basing our opinions on identifiable evidence. The usefulness of this skill transcends the walls of the classroom. In the world beyond the school gates, the ability to infer will serve students well in their interactions with others on personal, social, and business levels.

INFERENCE EXAMPLES

Explore these examples of inferencing in action based on a simple statement alongside the justification for the inference. More inferences can be made from them than just those stated, so see if you can come up with any others.

Example: “The window is open, and a cool breeze is coming in.”

Inference: The weather outside is likely nice and cool.

Justification: Based on the evidence presented in the sentence, the open window and cool breeze, students can draw an inference about the weather outside.

Example: “The main character’s heart is pounding, and their palms are sweaty.”

Inference: The main character is likely feeling nervous or anxious.

Justification: Students can infer the main character’s emotions based on the evidence presented in the sentence, the physical symptoms of a pounding heart and sweaty palms.

Example: “The dog is barking and growling at the mailman.”

Inference: The dog is likely feeling protective or territorial.

Justification: Based on the evidence presented in the sentence, the dog’s behavior towards the mailman, students can make an inference about the dog’s emotions and motivation.

These examples can be used to encourage students to practice making inferences based on evidence from a text. Teachers can use these examples to guide students through the process of identifying clues, drawing conclusions and inferring.

Year Long Inference Based Writing Activities

Tap into the power of imagery in your classroom to master INFERENCE as AUTHORS and CRITICAL THINKERS.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (26 Reviews)

This YEAR-LONG 500+ PAGE unit is packed with robust opportunities for your students to develop the critical skill of inference through fun imagery, powerful thinking tools, and graphic organizers.

HOW IS INFERENCE TAUGHT?

Learning to apply inference is not easy. For this reason, it is essential to make the process as explicit as possible for our students to gain a firm grasp of it. One effective means of teaching inference is to perform a kind of reverse engineering process. Begin by ensuring the students understand that:

- Our answers must be supported by clues

- These clues must be added to what we already know

- More than one correct answer is possible.

Higher-level reading comprehension questions often ask students to draw on their powers of inference, especially in the why and how questions posed or questions concerned with their thoughts and opinions.

Often students infer answers without being aware they are engaged in inference. For this reason, draw attention to how they arrived at their answers. Ask them how they ‘inferred’ their answer. This means they must explain how they arrived at their answer without referencing explicit information in the text. Ask them further questions to prompt how they arrived at their answer.

Encourage them to point to the clues and implicit information in the text that led them to their conclusion. Here, we are working to uncover the mysterious inference process by illuminating it.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PREDICTING AND INFERRING?

“PREDICTING and INFERRING are often confused, but they are not interchangable concepts.

Predicting is the process of asking what might happen next based on what we already know from inside and outside the text. Inferring is more a process of enquiring as to what the author meant?

Predicting focuses more on the WHAT whereas Inferring is more about the WHY”

— LITERACYIDEAS.COM

Read through these examples to clearly see the difference between a well-considered educated guess that doesn’t jump to conclusions (an inference) as opposed to a hunch. (a prediction)

Always keep an open mind when considering predictions and inferences, as quite commonly, they can arrive at the same outcome which is fine.

Example: A student sees a dark cloud in the sky.

Prediction: It is going to rain.

Inference: The weather is likely going to change, and it may rain.

How are they different? In this example, a prediction is a guess or assumption about a future event based on available information. On the other hand, an inference is a logical conclusion drawn from evidence already present. In this case, the dark cloud is evidence that the weather is changing, and the inference is that it may rain.

Example: A student watches a video of a person skiing down a steep slope.

Prediction: The person will fall.

Inference: Skiing down a steep slope is dangerous.

How are they different?: In this example, a prediction is a guess or assumption based on available information about a future event. On the other hand, an inference is a logical conclusion drawn from evidence already present. In this case, the fact that skiing down a steep slope is shown to be dangerous is evidence that the activity has risks, and the inference is that this is an important consideration for anyone who wants to try it.

Example: A student sees a group of people gathered around a table with a cake on it.

Prediction: They are celebrating someone’s birthday.

Inference: They are likely having a party or celebration.

How are they different? In this example, a prediction is a guess or assumption about a specific event based on available information. On the other hand, an inference is a logical conclusion drawn from the evidence in this scene. In this case, the group of people gathered around a table with a cake is evidence that they are likely having a party or celebration, and the inference is that it may not necessarily be a birthday celebration.

WHAT TO DO BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER READING

INFERRING BEFORE READING

ART STYLE What does the cover artwork tell us about potential characters, setting, genre, audience? What leads us to these conclusions.

TITLE AND TYPOGRAPHY Has the author gone for a whimsical fun title and font style or a bold, clear style? What might this have to do with the text? What clues does the text size and style tell us about the audience they are targeting?

BLURB what hooks or strategies have been used in the blurb to give us some insight into the story. What obvious questions remain unanswered from the blurb? Why might have these decisions been made?

INFERRING DURING READING

ACTION & REACTION If an act or event occurs within the test, note it down or have a shared conversation if reading within a group to decipher your thinking and reaction.

MARK YOUR TEXT Whether you use post-it notes, pencils or otherwise books are meant to be dissected. Use it as a physical resource at times to identify points to question, challenge and infer over.

LITERAL VS INFERENCE Read a challenging paragraph, and discuss it as a literal text, and then re-read it as a metaphorical piece. What is the difference? If any, and why?

INFERRING AFTER READING

LITERAL VS INFERENCE Read a challenging paragraph, and discuss it as a literal text, and then re-read as a metaphorical piece. What is the difference? If any, and why?

PRE-READING REFLECTION Were your expectations met from the pre-reading inference? Do you think this was intended by the author? What impact did this have?

TIPS FOR MAKING WISE INFERENCES

- Look for clues: When trying to make an inference, it’s important to look for clues that will help you figure out what’s going on. These could be things like a character’s actions, what they say, or the story’s setting.

- Connect the dots: Making an inference is like connecting the dots between the clues you find. It would be best to look for patterns and connections between different pieces of information to help you understand what’s happening.

- Use your own experience: Sometimes, the best way to make an inference is to use your experience. If you’re reading a story about a character going through a tough time, you can think about a time when you or someone you know went through something similar.

- Consider different perspectives: Inferences require you to think about different perspectives. This means trying to see things from the point of view of other characters and thinking about how their experiences and beliefs might affect their decisions.

- Be flexible: Making reasonable inferences means being willing to change your mind as you get more information. It’s important to be open to different explanations and interpretations of what’s happening and to be willing to change your initial assumptions as you learn more.

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your students’ inferencing skills.

INFERENCE ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS

Riddles

Setting riddles to solve is an excellent way for students to gain the necessary practice to hone their skills in inference. The stronger the students are, the more complex the riddle set can be – this makes for easy differentiation for various abilities. Developing this ability to solve riddles requires students to grow in confidence in reading for inference. Riddle-solving can be a great introductory activity on the subject of inference and can demonstrate to students lacking confidence that they already have some understanding of how the concept works. READ SOME GREAT CLASSROOM RIDDLES HERE

Show, Don’t Tell

We often urge our students to “Show, Don’t Tell!” in their writing. As their writing skills improve, we want them to move away from describing the characters in their stories with long lists of adjectives in favor of revealing their characters through the things they do and say.

To help students develop their ability to read inference, set them the task of identifying a character’s traits in a story exclusively through the things they do and say. This excellent reading extension activity can be easily used as homework. Students can work through a story, recording the information in three columns entitled: Character, Trait, Evidence. Remind students they are looking for implicit evidence, not things the writer has stated explicitly in the narration.

You can also bridge this reading activity into writing. Have students write short paragraphs about a personal experience. Tell them not to state any of the emotions they experienced explicitly. Instead, have them write details that help the reader understand how they felt.

Have student volunteers share their writing and briefly discuss each piece. What details helped the reader to understand what the writer was going through? What other details could be added to the writing to enhance this?

Give it to Me Straight! Making inferences Task.

This activity works well as an extension of the previous exercise and is basically an inversion of Show, Don’t Tell! In this exercise, students must translate a few inference sentences into explicit statements. The examples of inference identified in the previous activity will serve well as the material here. This exercise helps students recognize precisely what is being implied in this often very subtle means of communication.

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words – Visual inference questions.

For this activity, pop into the kindergarten library and grab yourself some picture books. Ignore the inevitable eye-rolls and moans of derision of the students in front of you and explain to them that you’re going to give each of them a book, and they are going to ‘read’ the books to each other.

Children’s book illustrators are masters of inference. They tell stories through the skilful use of visual clues. Students must become a translator of these visual clues into words. Encourage stronger students to also translate the inference in the picture into their narration by avoiding explicitly stating things.

You can also do a variation of this task by providing students with captionless photographs or pictures and asking them to tell the story of the picture. Students can compare and contrast their inferences for each picture.

Inference in film

Authors have the luxury of writing endless chapters to paint pictures in our minds and tell a narrative. Film-makers do not have this luxury and are both bound by more restraints but given a more bottomless toolbox to tell a story. If you have ever listened to a director’s commentary whilst watching a film, you will appreciate the effort a filmmaker makes to use inference in their craft.

Everything included in a film is there for a purpose; the setting, background props, dialogue, and music are all calculated decisions used to build emotion and story. Sometimes what is left unsaid or unshown can also tell us more than what is actually in the film.

Inference and film are a match made in heaven in the classroom and will provide your students with the analytical skills to watch films at a much deeper level.

A WORD ON GUIDED READING

Guided reading works exceptionally well for teaching inference. Working with small groups of students at similar reading levels, you can effectively improve their ability to read a text for inference. In your guided reading groups:

- Discuss the importance of the title to the meaning of the text

- Discuss and compare the different interpretations of the text by other group members and how they arrived at their interpretations.

- Discuss the motivations of characters in the stories and the relationships between those characters.

- Encourage students to explain how they arrived at their opinion by asking, ‘How do you know?’

- Encourage students to activate prior knowledge through timely discussions.

Be sure to offer opportunities for reading inference across a range of genres. While fictional stories offer the most significant number of opportunities to read for inference, other genres also offer opportunities. Expository texts, for example, promote opportunities for more conscious inference-making.

You can significantly help students by modelling answers and by ‘thinking aloud’ to show your students how you arrived at your conclusions. When students are engaged in making their own inferences, encourage them by asking inference-generating questions that will propel them along the path. READ OUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO TEACHING GUIDED READING HERE

MAKE THE IMPLICIT EXPLICIT

The art of inference is a skill, like most skills, that improves with practice. There will be ample opportunity to reinforce inference skills through the course of the average English lesson as students engage in discussion, complete comprehension exercises, study poetry etc. Even though inference skills will be regularly called upon in lessons that are not primarily focused on developing this skill, it is still essential that some discrete lessons focus primarily on inference.

The inference is often complex for students to understand initially, especially for younger students. It can often slip just beyond their grasp due to its subtle nature. Begin with baby steps. Try to climb down the ladder of abstraction and peel back the layers to make the implicit explicit. With practice, students will soon be able to move beyond recognizing and reading inference in the works of others to incorporate it into their work.

TOP TIPS FOR TEACHING INFERENCE IN THE CLASSROOM

- When it comes to teaching inference, it’s important to start with examples that ignite your students’ imaginations. Choose texts or situations that are rich in detail and nuance, that can spark your students’ curiosity and get them excited about the process of making inferences.

- One key to helping your students develop strong inference skills is to emphasize the importance of evidence. Encourage your students to look closely at the details and evidence provided in the text or situation and to use this evidence to support their inferences.

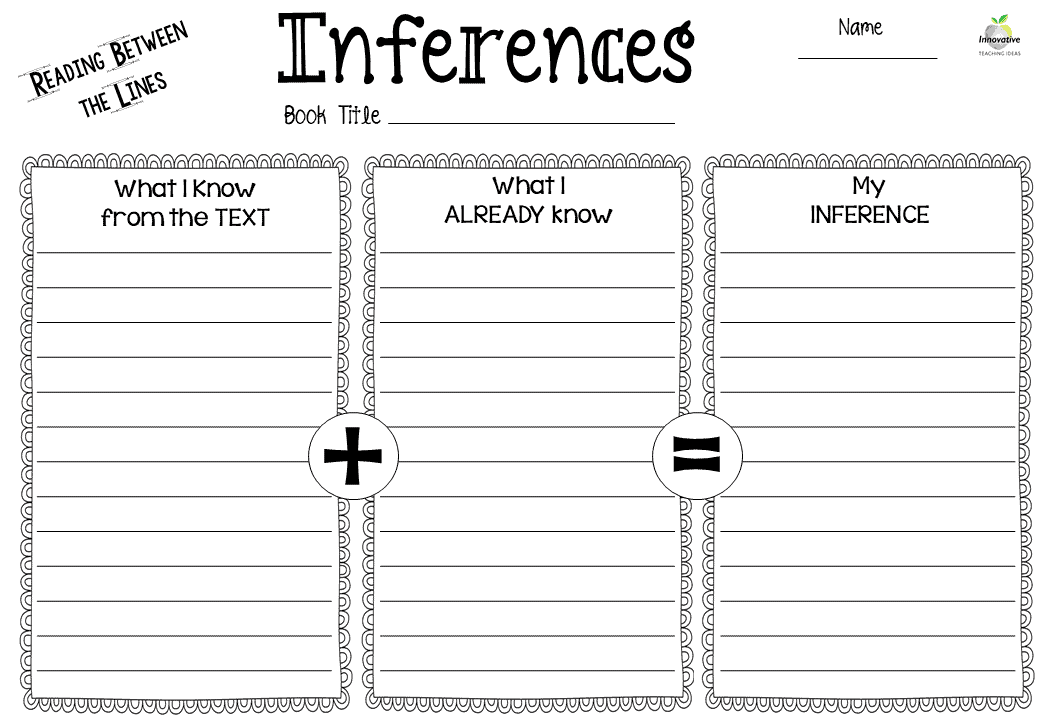

- Graphic organizers can be powerful tools for helping your students visualize and organize their thoughts as they make inferences. Consider using tools like T-charts, Venn diagrams, or concept maps to help your students see the connections between different pieces of evidence.

- Of course, the most crucial aspect of teaching inference is providing your students with plenty of opportunities to practice. Use a variety of engaging materials to give your students a chance to develop and refine their inference skills and encourage them to discuss their inferences with their peers.

- Finally, don’t forget the importance of reflection and discussion. Please encourage your students to share their inferences with each other and to explore the different perspectives and interpretations that can arise from the same set of evidence. By fostering a culture of curiosity and reflection, you can help your students develop strong inference skills that will serve them well throughout their lives.