This article is part of the ultimate guide to language for teachers and students. Click the buttons below to view these.

What Is Grammar?

Grammar is often defined as the system or underlying structure of a language. It describes the principles that underpin the language that, if these are understood, help us to use the language effectively to communicate precise meaning to other speakers of the language.

Grammar as a concept covers a vast terrain that can be helpfully divided into the two subcategories of morphology, which concerns itself with the form and structure of words, and syntax, which looks at how words are arranged into sentences.

Of course, as with so many language-related topics, things can get extremely complicated. While many teachers understand grammar as ‘the rules’ of the language, they will also be aware that language is constantly evolving and that there are often wide discrepancies between prescriptive ‘rules’ of grammar and the everyday spoken and written use of that language.

This ever-changing nature of living languages notwithstanding, grammar can provide a valuable practical guide for our students to help them communicate effectively in both speech and writing.

There are lots of theoretical cul-de-sacs in grammar. While these are often fascinating neighborhoods to explore, they frequently aren’t worth the time investment of our students at this stage.

In these articles, we’ll focus on exploring grammar from the point of view of getting the most bang for the student’s buck.

But, first, let’s take a look at just why grammar is worth any time investment at all.

Why is it important for students to understand grammar?

Here are just a few of the reasons why students should hone their understanding of grammar. Grammar helps us to:

1. Communicate Effectively

Good grammar helps us avoid miscommunication. Language is rich in ambiguity, and misunderstandings are frequent. Applying grammatical principles to their writing enables students to control better what they express and how it is interpreted by the reader.

2. Builds Trust and Authority

Poor use of grammar doesn’t exactly inspire the confidence of the reader. Generally, when we write, we want to form a relationship of trust with our readers. We want them to have faith in the person behind the words. This trust helps lend authority to the ideas expressed. Poor grammar may call the writer’s competency into question.

3. Convey Respect to the Audience

Like manners, how stringently we apply the formal principles of grammar can depend on our audience. For example, a postcard to a friend will have a different language register than an academic essay. Understanding this is particularly important for our students as much of their writing will, by definition, be academic in nature. Frequently, their audience will be teachers, professors, examiners, etc.

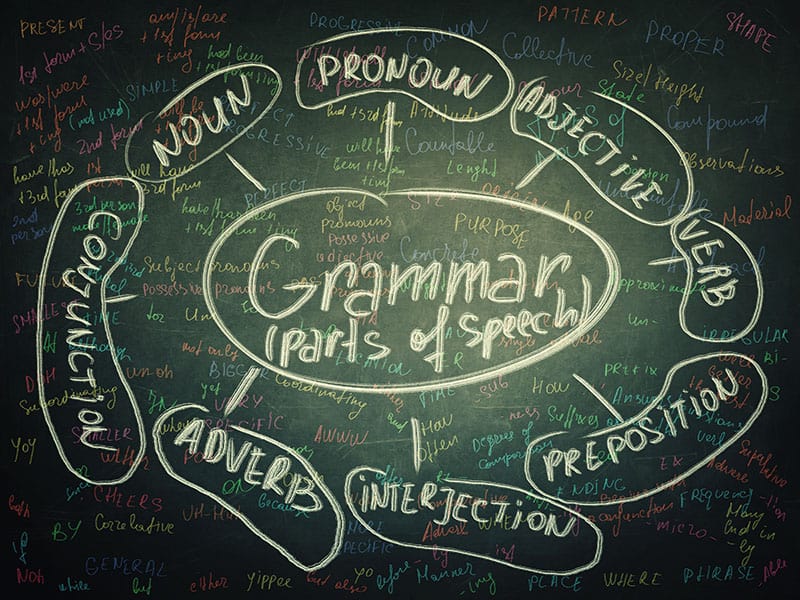

Parts of Speech: The Building Blocks of Grammar:

Parts of speech are the fundamental building blocks of language. It is necessary that our students first understand these before understanding how they fit together in sentences. be sure to read our complete guide to parts of speech here.

Before beginning the complex work of verb conjugations, it is worth reviewing student’s understanding of the parts of speech.

In English, we typically recognize eight specific parts of speech. These are:

- The Noun: the naming words for people, places, and things, e.g. writer, Portugal, happiness.

- The Verb: words used to describe an action, a state, or an occurrence, e.g. ran, thought, became.

- The Adjective: words that name attributes or describe nouns, e.g. gentle, tasty, zealous.

- The Adverb: a word that modifies or describes a verb, adjective, or another adverb e.g. frequently, mysteriously, wisely.

- The Pronoun: a word that stands in for a noun or noun phrase, e.g. she, that, anybody.

- The Preposition: words that show the relationship between nouns or pronouns and other parts of a sentence, e.g. on, for, through.

- The Conjunction: a word that joins parts of a sentence, phrases, or other words together, e.g. and, or, although.

- The Interjection: an abrupt remark, aside, or interruption, e.g. ouch, ahem, phew.

Most of these parts of speech can be further divided into subtypes. While we will take a closer look at some parts of speech in this article, to get a comprehensive analysis of these essential grammatical elements, check out our Ultimate Guide to Parts of Speech here.

Practice Teaching Activity: Parts of Speech Identification

When students become proficient at recognizing the different parts of speech in a sentence, they will be well on their way to understanding how the grammar of English operates.

To facilitate this, first, work through the different definitions and activities with the students from the article linked to above.

Once students are ready, give them a copy of a sample text. In groups, students can work through the text, categorizing each word according to which part of speech it is.

This will require the students to perform a close reading of the text and consider carefully the function of each word in each sentence. Valuable practice indeed!

Verbs

While our guide to the parts of speech comprehensively covers each word category and its properties, some further grammatical detail on verbs will be required to make our coverage of this complex word type complete.

There is a bit of controversy over how many tenses English has. Technically, linguists argue, there are only two inflected tenses in English: the past and the present.

The future is not considered a true tense as there is no future tense verb ending. The future is indicated in English by using modal auxiliaries such as will and shall often with the present term verb form.

But let’s not get too caught up in all this linguistic rigmarole. Let’s stick with the practical and useful. For all practical purposes, there are three main tenses in English:

- The past tense

- The present tense

- The future tense

Verbs: Conjugations

Verb tenses let us know when the action described by the verb happens. To indicate the tense a verb is in, it must be modified or conjugated in some way. Conjugation is when we change the verb to reflect a different tense, person, number, or mood.

We are going to examine the different tense forms later in this article, but, first, we’ll need to know what the base form of the verb is (visible in the infinitive form) and look at the principal parts of the verb.

Verbs: The Infinitive

This form of the verb includes its most basic form preceded by to. This basic form of the verb is sometimes called the base form. This is the form that we turn to when we are looking up the verb in a dictionary.

The full infinitive form is easily recognizable as it is the base form of the verb preceded by to. Though we are used to thinking of to as a preposition, in this context, to is not operating as a preposition. Instead, it is serving as ‘the sign of the infinitive’.

Let’s take a look at a few examples.

I like to eat a late breakfast on my day off.

She is confused as she has so many options to choose from.

We decided to go home.

To Boldy Split or Not To Boldly Split an Infinitive

One rule that is commonly repeated to students is that they should never ‘split’ the infinitive. But, what exactly does it mean to ‘split an infinitive’ and is this a hard and fast rule?

Splitting an infinitive involves placing an adverb between the to and the base form of the verb.

We can find a well-known example of a split infinitive in the tagline from the old Star Trek TV series:

To boldly go where no man has gone before.

Here, we can see that the adverb ‘boldly’ (helpfully in bold!) is placed between the to part of the infinitive and the base verb go. This is an example of a split infinitive and is frowned upon by the more pedantic among the teaching tribe.

The pedantic grammarian would insist on ‘to go boldly’, rather than the much more rhythmically satisfying ‘to boldly go’. But is this really such a crime against grammar?

Traditionally, the general rule is that nothing should come between the to and the verb when using the infinitive. However, what is acceptable, grammatically speaking, changes with time and it is now common to see infinitives split, especially in informal writing.

A good rule of thumb is that split infinitives are okay where they are necessary for meaning or flow. Sometimes, the convoluted structural contortions required to avoid splitting an infinitive can result in clumsy sounding sentences. Let good taste be the ultimate judge!

The Principal Parts of a Verb

The principal parts of the verb are the four main verb forms that students must know in order to correctly conjugate verbs. Our students need to know the parts of the verb to correctly form the verb tenses.

Tense refers to when the verb happened. For example, while the verb form in the sentence ‘They close the door,’ conveys the action happening in the present tense, the sentence, ‘They closed the door,’ expresses the action in the past tense. These forms of the verb (e.g., close and closed) are what we mean when we talk of verb tense.

As we mentioned earlier, technically there is no future tense in English, which is why we see only the present and the past parts mentioned below. The future ‘tense’ is formed using present tense forms of the verb along with will/shall – but more on that later!

There are four principal parts of verbs in English are:

- the present

- the past

- the present participle

- the past participle.

i. The Present

The present is the first principal part or base form of the verb. Also known as the root, it is this form of the verb we will find listed in the dictionary.

The base is used as-is for most forms in the present tense, including first person (I, we), second person (you), and third-person plural (they).

For example:

I dance

we dance

you dance

they dance

However, in the third-person singular (he, she, it), we add the letter -s at the end of the base. This is the only time the base form changes in the present tense.

For example:

he dances

she dances

It dances

ii. The Past

How the past tense of a verb is formed in English will decide whether it is a regular or irregular verb. Regular verbs are those that follow the typical pattern for the past tense as described here. Those that break with this pattern are known as irregular verbs (e.g., went, ate, ran, etc.).

To form the past tense of regular verbs, we simply add -ed to the base form. However, if the verb ends in a silent e already, we only need to add -d.

In contrast with the present, the past tense does not change regardless of the number or person.

For example:

I danced

you danced

she danced

he danced

it danced

we danced

they danced

iii. The Present Participle

This is often referred to as the -ing form of the verb. They function as a part of a verb phrase and always need to be accompanied by an auxiliary verb (also known as a helping verb).

To form the present participle, you simply take the base form of the verb and add -ing.

So, for example, dance becomes dancing.

You will notice that the e at the end of dance is removed. If the word ends with a silent e, it is first removed before –ing is added.

Present participles combine with forms of the verb to be to form the progressive tense, which describes actions that are unfinished as yet or in progress.

For example:

I am dancing on the stage.

You are waiting for the end.

My father is watching television.

iv. The Past Participle

Past participles are formed in the same way as the past tense. That is, by adding -ed or d to the end of the verb.

While the regular form of the past participle is constructed by adding -d/-ed to the end of the base verb, however, there are also a number of irregular past participles to consider, e.g. done, eaten, felt, gone, known, said, thought, won.

Past participles can be found at work in the past perfect tense – among other tenses. This tense is used to describe actions that were completed before something else.

For example:

We had finished our homework before dinner.

Stephanie had travelled this road many times.

The manager closed the door but they had left already.

Practice Teaching Activity: Spot the Principal Part

This simple activity can be undertaken by students individually or in small groups and it requires little in the way of preparation.

Provide students with copies of books suited to their reading levels. On a sheet of paper, students create a table containing four columns. Each with a heading that corresponds to one of the principal parts of verbs, i.e. present, past, present participle, past participle.

Students then comb through the books identifying examples of each of the four parts of the verb in use within the text. They copy these onto their tables as examples illustrating each part.

Learning to quickly and precisely identify each part in this manner helps the student internalize how each part works; they will then be able to use these confidently and accurately in their own writing.

Person

In English, we conjugate verbs depending on the grammatical person used. Each of these ‘persons’ is represented by a pronoun. There are six of these ‘persons’ and they are:

| Grammatical Person | Pronouns |

| The First Person Singular | I |

| Second Person Singular | You |

| Third Person Singular | He / She / It / One |

| First Person Plural | We |

| Second Person Plural | You |

| Third Person Plural | They |

The form of the verb used will depend on the grammatical person referred to (as well as its tense – more on this later!).

While many of the verbs will follow regular conjugation patterns, some are entirely irregular. One of the most important of these is the verb to be:

| Grammatical Person | Verb To Be | Negative | Question Form |

| The First Person Singular | I am | I am not | Am I? |

| Second Person Singular | You are | You are not | Are you? |

| Third Person Singular | He / She / It / One is | He is not | Is he? |

| First Person Plural | We are | We are not | Are we? |

| Second Person Plural | You are | You are not | Are you? |

| Third Person Plural | They are | They are not | Are they? |

Note: Contracted forms of the verb to be are commonly used, especially in speech: I’m, you’re, he’s, she’s, it’s, one’s, we’re, they’re.

TENSE

Now students understand the four principal parts of the verb, they will be ready to dig into the tenses in more detail.

Each of the three main tenses of the past, present, and future can be divided further into four distinct forms:

- Simple

- Continuous

- Perfect

- Perfect Continuous

Below we will take a look at each tense. We’ll begin with the present, as it contains the base form.

The Present Tense

The present tense describes a current state of being or occurrence. Adverbially, it is right now, at this very moment!

While this definition is straightforward, there’s a little more to it when considering the four different forms we mentioned.

1. The Present Simple

We use the simple present tense in two main instances:

i. When something is happening right now, or;

ii. When something happens regularly or without stop.

To form the present simple: use the base form of the verb and add -s/-es in the third person singular.

For example:

She leaves for work early in the morning.

I walk to school.

We play chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add do/does and not in front of the base form of the verb.*

She does not leave for work early in the morning.

I do not walk to school.

We do not play chess at the weekend.

*do not and does not are often contracted to don’t and doesn’t

To form the question: put do/does in front of the sentence subject, followed by the base form of the verb.

Does she leave for work early in the morning?

Do you walk to school?

Do we play chess at the weekend?

2. The Present Continuous

This tense is used to show that an action is happening now and is ongoing. It can also indicate that the action may continue in the future.

Also known as the present progressive, some common uses of this tense include:

i. Describing things happening at this moment

ii. Describing temporary situations

iii. Referring to habitual occurrences

iv. Future arrangements

To form the present continuous: use the verb to be followed by the present participle form.

For example:

She is leaving for work early in the morning.

I am walking to school.

We are playing chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not between the verb to be and the present participle.*

She is not leaving for work early in the morning.

I am not walking to school.

We are not playing chess at the weekend.

*is not and are not are often contracted to isn’t and aren’t

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb to be.

Is she leaving for work early in the morning?

Am I walking to school?

Are we playing chess at the weekend?

3. The Present Perfect

We use this tense to refer to something that:

i. happens at an indefinite time in the past, or;

ii. began in the past and continued to the present.

To form the present perfect: add have/has in front of the past participle. An important point to note is that with the present perfect you cannot be specific about when the event happened.

For example:

She has left for work early in the morning.

I have walked to school many times before.

We have played chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not between the verb has/have and the past participle.*

She has not left for work.

I have not walked to school.

We have not played chess.

*has not and have not are often contracted to hasn’t and haven’t

To form the question: Invert the subject and the verb has/have.

Has she left for work?

Have I walked to school?

Have we played chess?

4. The Present Perfect Continuous

This tense is used to speak about something that began in the past and in ongoing at the present moment. It is also sometimes termed the present perfect progressive tense.

Adverbs such as ‘recently’ and ‘lately’ are frequently used with this tense to help indicate that though the action started in the past, it continues in the now and, possibly, the future.

We can use the present perfect continuous to:

i. describe an action that started in the past and continues up to the present

ii. indicate that something happened recently

To form the present perfect continuous: combine has/have with been, followed by the present participle.

For example:

She has been leaving for work early in the morning.

I have been walking to school.

We have been playing chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: Add not between the verb has/have and the been.*

She has not been leaving for work early in the morning.

I have not been walking to school.

We have not been playing chess at the weekend.

*has not been and have not are often contracted to hasn’t been and haven’t been

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb has/have.

Has she been leaving for work early in the morning?

Have I been walking to school?

Have we been playing chess at the weekend?

The Past Tense

The past tense places events or states of being in the already happened category. Again, this tense comes in four distinct flavors.

1. The Past Simple

The past simple is also known as the simple past, past indefinite, and the preterite. Among the uses of the past simple are to show:

i. a completed action in the past

ii. a duration of time

iii. habits in the past.

To form the past simple: add -d/-ed to the end of the base verb form (where the verb is regular).

For example:

She left for work early in the morning.

I walked to school.

We played chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add did not in front of the base form of the verb.*

She did not leave for work early in the morning.

I did not walk to school.

We did not play chess at the weekend.

*Note: the contracted form didn’t is widely used in place of did not, especially in informal speech.

To form the question: place did in front of the sentence subject followed by the base form of the verb.

Did she leave for work early in the morning?

Did you walk to school?

Did we play chess at the weekend?

2. The Past Continuous

Sometimes called the past progressive, this tense is used to refer to an ongoing state or action that happened in the past. Two common uses of the past continuous include to:

i. show a longer action was interrupted

ii. express two actions happening at the same time.

To form the past continuous: combine the past tense of the verb to be (was/were) with the verb’s present participle (-ing).

For example:

She was leaving for work early in the morning.

I was walking to school when I noticed it was raining.

We were playing chess when she rang.

To form the negative: add not between the verb to be and the present participle.*

She was not leaving for work early in the morning.

I was not walking to school when I noticed it was raining.

We were not playing chess when she rang.

*was not/were not are often contracted to wasn’t/weren’t, especially in informal speech.

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb was/were

Was she leaving for work early in the morning?

Was I walking to school when I noticed it was raining?

Were we playing chess when she rang?

3. The Past Perfect Tense

Also known as the pluperfect, this tense is used to talk about actions that were completed before some point in the past. The past perfect is often used to

- indicate the order of two events

- express a condition and a result

To form the past perfect: we use had before the past participle.

For example:

She had left for work before breakfast time.

I had walked to school before it started raining.

We had played chess together.

To form the negative: add not between had and the past participle.*

She had not left for work before breakfast time.

I had not walked to school before it started raining.

We had not played chess together.

*had not is often contracted to hadn’t

To form the question: invert the subject and had.

Had she left for work before breakfast time?

Had I walked to school before it started raining?

Had we played chess together?

4. The Past Perfect Continuous

Also known as the past perfect progressive, this tense shows an action that started in the past and continued up until another point in the past. This tense is useful for showing the

i. duration of something in the past

ii. cause of something in the past

To form the past perfect continuous: combine had been with the present participle.

For example:

She had been leaving for work when the phone rang.

I had been walking to school for twenty minutes when it started raining.

We had been playing chess when the argument started.

To form the negative: add not between the had and the been.*

She had not been leaving for work when the phone rang.

I had not been walking to school for twenty minutes when it started raining.

We had not been playing chess when the argument started.

*had not been is often contracted to hadn’t been

To form the question: invert the subject and had.

Had she been leaving for work when the phone rang?

Had I been walking to school for twenty minutes when it started raining?

Had we been playing chess when the argument started?

Year Long Inference Based Writing Activities

Tap into the power of imagery in your classroom to master INFERENCE as AUTHORS and CRITICAL THINKERS.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (26 Reviews)

This YEAR-LONG 500+ PAGE unit is packed with robust opportunities for your students to develop the critical skill of inference through fun imagery, powerful thinking tools, and graphic organizers.

The Future Tense

The future tense is generally used to refer to things or states that will happen or are expected to occur in the future. Let’s take a look.

1. The Future Simple

There are actually two forms of this tense. Both refer to specific times in the future and, though they are sometimes used interchangeably, they can also be used to express distinct differences in meaning. These will become apparent to the students with practice. Note too that the second variant described below is a little more informal than the first.

The future simple is used to refer to:

i. an action or state that will begin and end in the future

ii. express a plan

iii. make a promise

iv. make a prediction

To form the first variant of the future simple tense: place will before the base verb form.

For example:

She will leave for work early in the morning.

I will walk to school.

We will play chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not in between will and the base form of the verb.*

She will not leave for work early in the morning.

I will not walk to school.

We will not play chess at the weekend.

*will not is often contracted to won’t

To form the question: invert the subject and will.

Will she leave for work early in the morning?

Will I walk to school?

Will we play chess at the weekend?

To form the second variant of the future simple tense: combine the verb to be with going to, followed by the base verb form.

For example:

She is going to leave for work early in the morning.

I am going to walk to school.

We are going to play chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not in between the verb to be and going to.

She is not going to leave for work early in the morning.

I am not going to walk to school.

We are not going to play chess at the weekend.

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb to be.

Is she going to leave for work early in the morning?

Am I going to walk to school?

Are we going to play chess at the weekend?

2. The Future Continuous

Sometimes referred to as the future progressive, as with the future simple, the future continuous has two distinct forms. These two forms are usually interchangeable.

The future continuous describes an action or state that will occur in the future for a specific length of time. It is often used to refer to:

i. an interrupted action

ii. describe parallel actions taking place

To form the first variant of the future continuous tense: place will be in front of the present participle.

For example:

She will be leaving for work early in the morning.

I will be walking to school.

We will be playing chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not in between will and be the base form of the verb.*

She will not be leaving for work early in the morning.

I will not be walking to school.

We will not be playing chess at the weekend.

*will not is often contracted to won’t

To form the question: invert the subject and will.

Will she be leaving for work early in the morning?

Will I be walking to school?

Will we be playing chess at the weekend?

To form the second variant of the future continuous tense: combine the verb to be with going to be, followed by the present participle.

For example:

She is going to be leaving for work early in the morning.

I am going to be walking to school.

We are going to be playing chess at the weekend.

To form the negative: add not in between the verb to be and going to.

She is not going to be leaving for work early in the morning.

I am not going to be walking to school.

We are not going to be playing chess at the weekend.

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb to be.

Is she going to be leaving for work early in the morning?

Am I going to be walking to school?

Are we going to be playing chess at the weekend?

3. Future Perfect

The future perfect is used to describe something that will happen before some other point in the future. Again, there are two distinct variants of this future tense form, but they are usually interchangeable.

The future perfect is frequently used to describe:

i. an action completed before something in the future

ii. how something will continue up until another action in the future.

To form the first variant of the future perfect tense: place will have in front of the past participle.

For example:

She will have left for work by the time I get up.

By nine o’clock, I will have walked to school.

We will have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over.

To form the negative: add not in between will and have.*

She will not have left for work by the time I get up.

By nine o’clock, I will not have walked to school.

We will not have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over.

*will not is often contracted to won’t

To form the question: invert the subject and will.

Will she have left for work by the time I get up?

By nine o’clock, will I have walked to school?

Will we have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over?

To form the second variant of the future perfect tense: combine the verb to be with going to have followed by the past participle.

For example:

She is going to have left for work by the time I get up.

By nine o’clock, I am going to have walked to school.

We are going to have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over.

To form the negative: add not in between to be and going to have.*

She is not going to have left for work by the time I get up.

By nine o’clock, I am not going to have walked to school.

We are not going to have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over.

*is not and are not are often contracted to isn’t and aren’t

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb to be.

Is she going to have left for work by the time I get up?

By nine o’clock, am I going to have walked to school?

Are we going to have played a game of chess by the time the weekend is over?

4. Future Perfect Continuous

Sometimes called the future perfect progressive, this tense also has two different forms which are largely interchangeable. With this tense, we project ourselves into the future and look back at the duration of an action.

The future perfect continuous can be used to refer to:

i. something that will continue up until a particular time in the future

ii. the cause of something in the future

To form the first variant of the future perfect continuous tense: place will have been in front of the present participle.

For example:

By ten o’clock, she will have been working for an hour already.

By nine o’clock, I will have been walking to school for twenty minutes.

We will be tired because we will have been playing chess for over an hour.

To form the negative: add not in between will and have.*

By ten o’clock, she will not have been working for an hour already.

By nine o’clock, I will not have been walking to school for twenty minutes.

We won’t be tired because we will not have been playing chess for over an hour..

*will not is often contracted to won’t

To form the question: invert the subject and will.

By ten o’clock, will she have been working for an hour already?

By nine o’clock, will I have been walking to school for twenty minutes?

Will we have been playing chess for over an hour?

To form the second variant of the future perfect continuous tense: combine the verb to be with going to have been, followed by the present participle.

For example:

By ten o’clock, she is going to have been working for an hour already.

By nine o’clock, I am going to have been walking to school for twenty minutes.

We will be tired because we are going to have been playing chess for over an hour.

To form the negative: add not in between the verb to be and going to have been.*

By ten o’clock, she is not going to have been working for an hour already.

By nine o’clock, I am not going to have been walking to school for twenty minutes.

We will be tired because we are not going to have been playing chess for over an hour.

To form the question: invert the subject and the verb to be.

By ten o’clock, is she going to have been working for an hour already?

By nine o’clock, am I going to have been walking to school for twenty minutes?

Are we going to have been playing chess for over an hour?

Verb Tense Practice Activities for Students

Practice is the only way students will be able to internalize the vast array of rules and patterns that underscore how the various verb tenses operate.

Below, you will find a selection of activities to help students develop their understanding of how the different tenses are formed and what they are used for.

1. The Verb Tense Timeline

This is a great way for students to visualise where each tense fits chronologically on a timeline.

You can do this by marking out a timeline outline on the whiteboard as below:

Past Now Future

Print out example sentences for each of the tenses, and, as a class, students discuss where each sentence would fit relative to each other on the timeline.

When they’ve decided on a suitable spot on the timeline, have the students stick the piece of paper in place on the whiteboard. Continue the process until all sentences have been assigned a position.

2. Quickfire Quiz

In this fast-paced, fun activity, students are organized into competing groups, and each team has a bell or buzzer.

Present a sentence to the class, and the first team to ring their bell or buzzer has an opportunity to identify the tense. A correctly identified tense sees a point awarded, with an incorrect answer resulting in a point deducted. The winning team is the team with the highest number of points at the end.

This activity is easily adapted for the specific level of the students. For example, the focus could be simply on identifying past, present, and future for younger students. For intermediate students, the focus could be on the four variants of a single tense. Advanced students could work on identifying all 12 variants across the three tenses.

3. Tell a Tale in Another Tense

Project a picture on the board that will serve as a writing prompt. Assign each student a specific tense to tell a story based on the image. Again, this activity is easily differentiated for the specific abilities of the class as a whole or the student as an individual.

When students have completed their story, ask them to swap their story with a partner who has been working on a different tense. Can the students rewrite their partner’s story in their assigned tense?

4. The Verb Lottery

This oral activity will give the students’ wrists some welcome respite. Write the names of all the verb tense variants on pieces of paper and dump them into a suitable container.

Students then take turns picking out a piece of paper at random and forming a sentence orally in that tense. This activity can easily be made competitive by first organizing the students into teams.

5. Snap!

This is based on the popular card game where players slap their hands down on matching upturned cards as quickly as possible. The winner of a hand adds the cards to their pile until one of the players ends up with all the cards.

In this version of the game, the cards are matched not by color, number, or suit but by verb tenses. Students make the cards by first writing sentences in the various verb tenses. When students see two upturned sentences that match according to tense (e.g. present perfect continuous), they slap their hand down on the upturned cards, shout snap, and claim the cards for their hand. This continues until one player wins the whole deck.

Now students have a good understanding of verb conjugations and how they work, it’s time to put this all together in the form of well-structured sentences. To help with that process, check out our Complete Guide to Sentence Structure here.